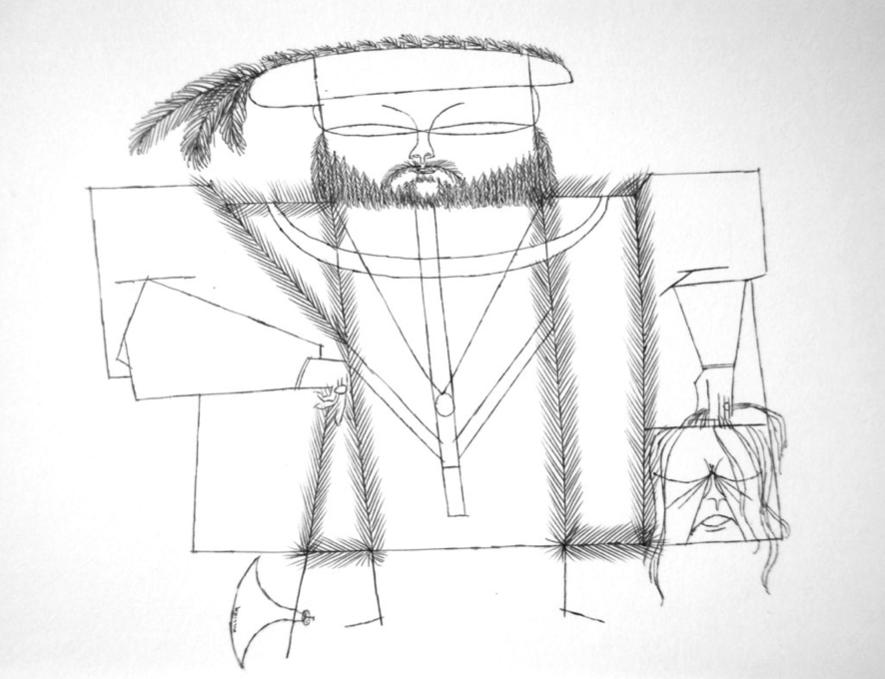

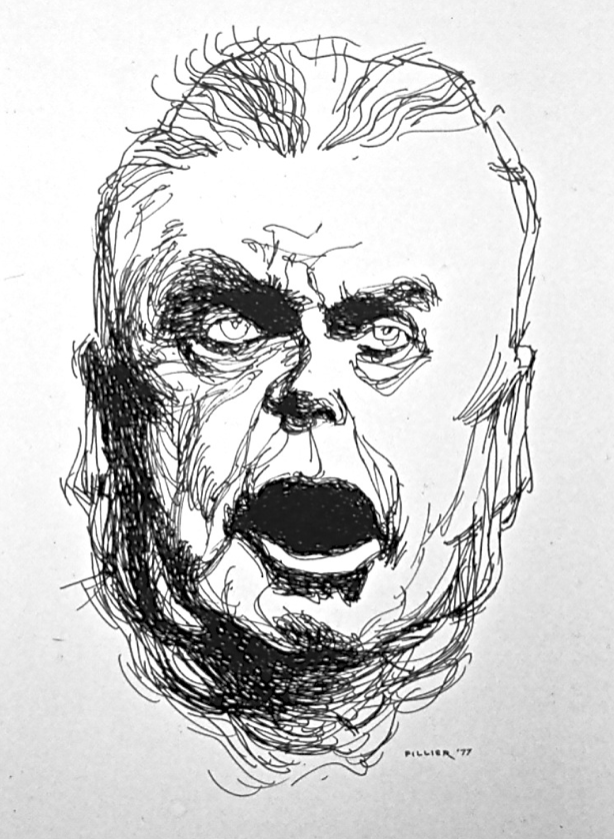

If you check through the several drawings of faces I’ve posted to date in this blog you will see that the approach is rarely ever the same. And that is a truth that applies to each and every one of several hundreds of faces I’ve drawn over five decades.

In part this is because every personality attempted is strikingly different. And in the other part it is intentional: my goal is always a rendering that is its own master of the page on which it appears. To that end I’ve always been willing to sacrifice consistency of style and technique. The only consistency I espouse is one of concept and the best possible realization of that concept. If I need to adapt line and crosshatched tones to achieve it, then that is where I must go, and I will need to forego my own egoistic concerns with always being predictable in the presence of other artists and critics.

My entire end-game as artist is to master every possible way a technique or media can be used—there is more artistically and aesthetically for me to gain if I set up a different problem every time out—solving the same problem over and over and over can only end, at least for me, in personal futility and boredom.

If that appears in any way to be a defence, or a rationalization of my preferences and approaches, then OK. I don’t mind. The singular face arrived at in the above drawing was well worth it.

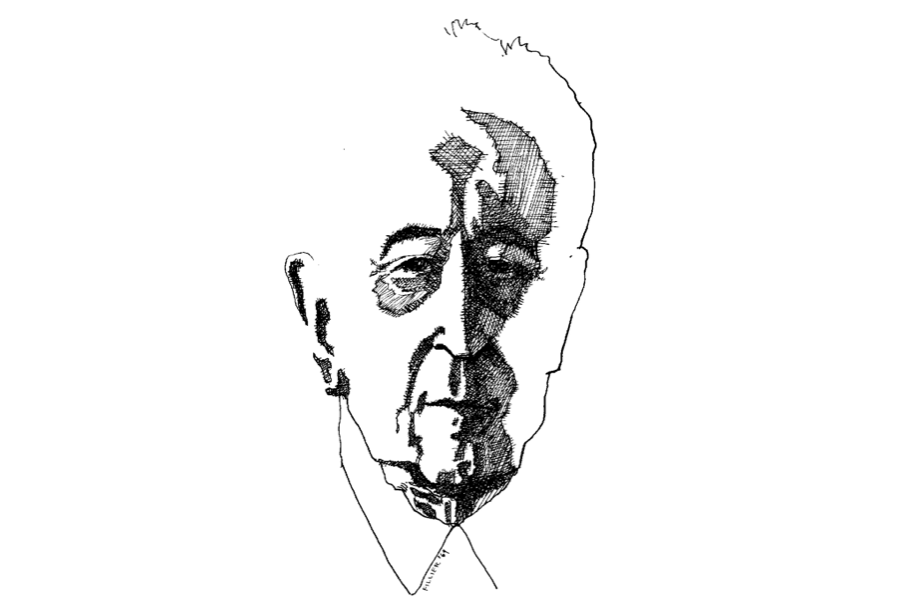

Here the subject was Arthur (Artur) Rubinstein, venerated as a master musician through much of the 20th century. In his latter years his face actually registered his incredible inner mastery of himself, of the piano keyboard, and especially of the music of his fellow compatriot Chopin. He had elevated himself into this sort of totem and symbol of power and indomitable endurance. He lived to be 95 and had performed publicly / internationally for eight decades.

My job was to find, amid the many public images of the man, that inner Artur and give it as profound an expression as possible at the moment of drawing.

This drawing, like most in my personal collection, has never before been publicly shown.