Fiddles and button accordions still grace many Newfoundland and Labrador kitchens. Not only because they evoke pleasant visual recollections of a past culture, but because they can be put to good use if a few friends drop by and tease / beg / bribe / cajole the host into a few toe-tapping tunes.

My maternal grandfather played both instruments, though I mostly recall his fiddling that followed a particular United Church Ladies Aid Supper/Social one evening in late July of 1950. The place: Flat Islands, Placentia Bay, NL.

After the sober, well-blessed, well-partaken, and typically abstemious Church Supper and Crafts Sale had raised the required funds, the long communal tables were taken apart and the centre of the school hall emptied of tables, desks, and chairs. They were stacked against walls or moved into the next classroom until enough space was available for a Square Dance. The term “Square Dance” was acceptable as it implied something formal, something full of etiquette and widely-accepted rules; whereas the word dancing, like card-playing, was generally avoided as it had something licentious and sinful about it, especially whenever it found mention in a Sunday sermon. To this end I’m surmising the word “scuff” evolved to replace “dance” as it, scuff, implied exercise rather than a purely self-indulgent pleasure.

Despite the word dancing being so overloaded with guilt, and despite there being only two actual Square Dances in the evening, one fisherman accepted the role of spoons and foot-stomp rhythm; another the push/pull bellows of a button accordion; for a ballad someone was always ready with mouth-organ, guitar and a local rendition of Wheeling West Virginia’s “Your Cheatin’ Heart” or “I’m Movin’ On”; but for the most part, Albert, my “Pop”, as we called him, rose to the incoming tide of the dance and fiddled until that tide, just like the one in the beach, receeded hours later. Much to Grandma Jane’s chagrin, though, and reverting to an old habit he’d sworn off, he also dragged on a cigarette or two, and whet his whistle from a secret little canteen that made the rounds.

With sunset, and oil lamps lit, those presbyterian feet grew wings at the ankles. And, like many of the top two buttons on the blouses, and the mens’ shirts with their sleeves also rolled up, windows and doors were loosened to lessen the body heat from a full house, and disperse the dust scuffled upward from the foot-worn, generations-worn wooden floor, despite its recent and thoroughly diligent mop and scrub.

And that is where another memory kicks in and dominates my recollection of that dance: nobody’s aunt in particular, but everyone’s adorable community aunt in general, a very agile, very senior Aunt Polly, in a polka-dot blouse (although, to render it more precisely, there were no dots but heads of black roses printed on white satin) danced in a trance. White hair tightly permed, with her scuffs, and swings, and wheels and swerves of black roses, she captured everyone’s eye as she served up her energies like alms to the wee hours of morning—so I’m told: this 10-year-old got dragged home early, got the rest of that yesterday’s tale by well garnished hearsay, the well-greased clothesline way.

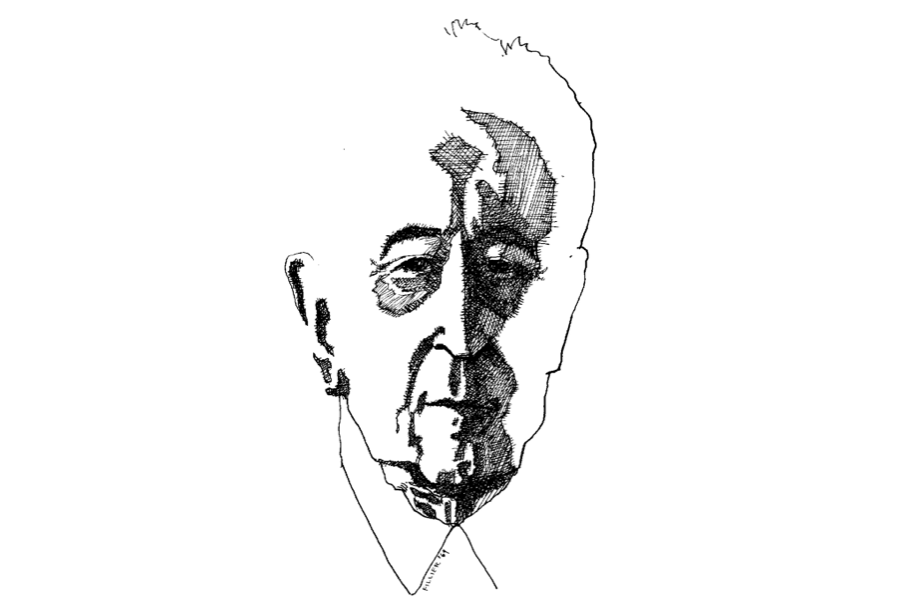

The figure in the attached drawing is not a portrait of my grandfather, though he was of that body type; nor is it an embodiment of Rufus Guinchard, a very well known NL fiddler from the 1970s and 80s who toured the world with fiddle, with Clyde Rose and other Breakwater Pressers, literally selling NL jigs and reels internationally, as well as published books; and it very definitely is not the rake thin Emile Benoit who was as clever with his mouth scat as Ella Fitzgerald. His infinite repertoire of tunes, often included his own compositions, or spur of the moment inspiration.

No. And it isn’t a drawing studied to death from a model in a studio. Nor photo based.

Like one of Emile’s electric scat-singing fiddling moments this is an innovation, a drawing “on the wing” and very much an Aunt Polly off the cuff / open-bloused scuff. It’s a drawing summoned up from memory, intuition, and imagination. So off the cuff as to be one of a kind. It’s one of my personal inventions. I have done quite a few of these Scott Scats. The lines and infinite little markings and squiggles are all drawn in white oil pastel on white paper. The deliberate goal is that the artist does not clearly see what is happening on the paper, doesn’t see where these absorbent, invisible oil pastel markings have built up deposits in scuffs, and scumbles, in stumbles and in false leads. Then the artist takes a large plump makeup brush, loads it with tempera powder, and charges with the élan of an elderly Aunt Polly onto the dance floor of the blank page.

Depending on how richly the oil pastel went down so do lines and tones appear when the loaded tempera in the brush drags over and gets sucked into that oil pastel. As the drawing begins to emerge magically—like a photo in a developer tray—the artist begins to see where it would be best to further develop shapes, shadows, forms. Or invest in a colour change with another of the set of four such brushes—one for each of black / blue / yellow / red .