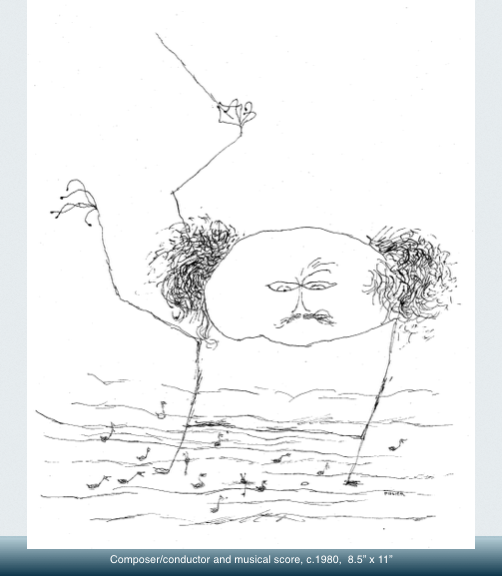

A monoprint is a one and only of . . . And this one a poem / visual / musician’s score all in the line/tone of one of a kind of . . .

A monoprint is a one and only of . . . And this one a poem / visual / musician’s score all in the line/tone of one of a kind of . . .

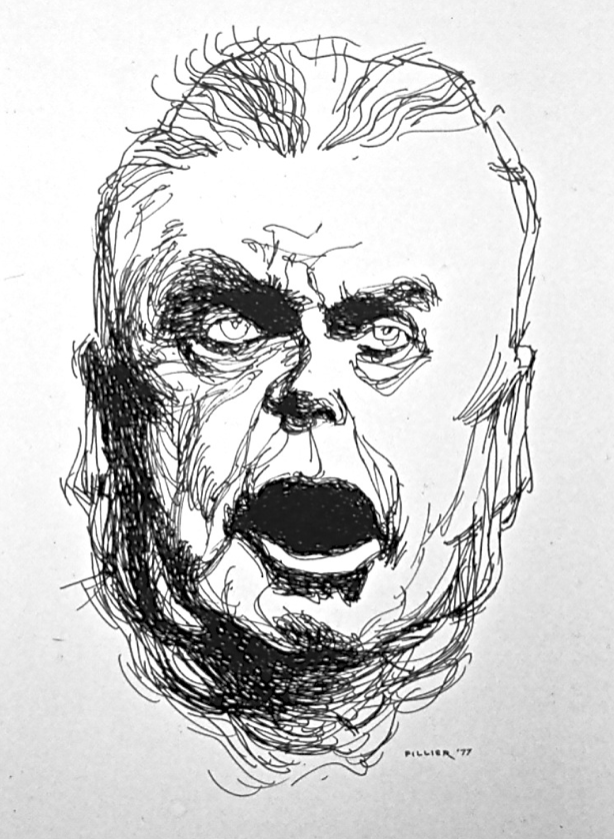

John George Diefenbaker, Canada’s 13th Prime Minister (1957-1963) as depicted in this smaller than life-sized drawing.

Made in 1977 it is in ball-point pen showing the elderly politician in the full, high-blown rhetoric that recalls his two decades plus of print media, and other coverage of him from radio and TV news sound clips.

It was drawn in my usual innovative style, meaning, that while I did have photo references at hand, I approached it without premeditation, or preparation, as to proportions and placement of features; I preferred to make whatever adjustments necessary along the way keeping the most casual, and unacademic, and unimpeded flow possible of pen to paper.

I was also keen to equally register the face I heard: After all, there was no such thing as a “still” photo of John Diefenbaker.

In a small label design office one summer job in Montreal, 1967, the Secretary / Receptionist told me, with much joy and enthusiasm, and obvious pride, she had been Mr. Diefenbaker’s secretary in an earlier decade in Saskatchewan. That curious piece of self-validation and self-verification on her part suddenly at this moment emerges as wanting into the bio-narrative of this drawing.

“Dief’s” song.

And yet … while I was fascinated by the visual impact of his delivery, nothing of his content found any resonance with me whatsoever. Nil. Zero. Zilch.

Snap? Sparkle? At the time, just short of them, in a 2005 watercolour from the crest of Signal Hill, St. John’s, NL.

A big sacrifice could remedy it. The picture had good bones and “nice abs” but somehow they must be retrofitted. Having the icon look good, or even handsome, was definitely not enough: I concluded I was being too precious about a full rendering of Cabot Tower itself; I needed to let go of catering to the standard tourist image and opt for a dramatic and drastic edit.

One day, no less than three years later then, I finally felt ready for the execution of the task, took steel ruler and utility knife to the project, and figuratively blew off / lopped off actually / the top half of the tower. Lovely irony that the munitions depot—gun-powder and cannon balls department—of former centuries retook the foreground by default back from the wireless monument.

How strange that that act of symbolic sabotage brought an immediate sense of getting much closer to essentials—the heart of the feeling when you’re standing in that parking lot on a bone-chilling, blustery day in late October, is with the weather and light recasting their characters every few minutes, and from all possible directions. Under those conditions the buildings, and you yourself, shrink to minor shivering incident: and if you’re paying proper attention, clouds, sun, rain, wind, and the huge space atop the hill all have “call of the wild” voices.

Instead of discarding the atmospheric clouds painted on either side of, and above the tower, I decided to salvage them, though I chose to continue lopping and chopping until there were just five concentrated segments available for precision pasting. The image itself seemed to have special delight in, and much preferred a composition with those segments not taking the position or orientation in which they’d been painted. Finally, lots of sharp precise edges presided and inside them free-flowing watercolour. Rough trade, the oyster’s outer shell, and inside all musical cool and mother-of-pearlish. Brushwork over brickwork. Art above craft.

Snap and sparkle earned and won.

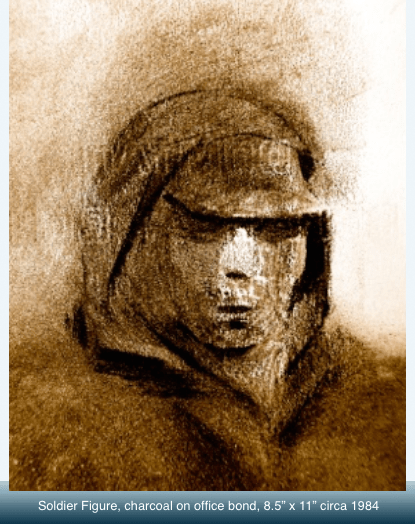

This face is a stand-in, an emblem, a token of many an unlikely, unsung hero, an unknown soldier. They’re in many of our family histories.

It formed itself on a sheet of paper on my drawing table one day early in the 1980s. Unbidden, unplanned, and certainly the most unexpected result of approaching a blank sheet with intent to draw from a blank mind—when unable to inspire an image by any other means I frequently do my own version of ‘automatic’ writing and drawing; in this instance ending up with the kind of presence a Ouija Board supposedly can summons.

My right hand made motions across, and up and down the page with soft charcoal, discovering a head and shoulders, innovating it, defining it on the fly but allowing it to be what it wanted to be, and stopping while it was yet arresting and spectral. I drag-wiped some areas with a tissue to unify them and add atmosphere, or the suggested swirl of an arriving figure, et, le voilà, I emerged at an unexpected place, a startling meditation on the numbness, the horrific milieu of trench warfare.

Perhaps it manifested itself out of my childhood school-days from the many iterations of NL’s tragic day at Beaumont Hamel, France, July 1, 1916. I didn’t need to add, nor attempt to remove, any of the original markings—it was already by impulse both perfect & imperfect, complete & incomplete, and likewise, also exhausting & enervating: a figure with masked emotions, an icon or a logo of extreme ennui, a doomed figure, a corpse-in-waiting.

The original, being charcoal, was black and grey-toned. About twenty-five years later, having decided it had enough impact to survive as a drawing, and when filing it on computer, I flipped it over into sepia and decided I preferred it so: having a little colour (life? hope? heart-beat?) somehow stayed the monochrome youth this side of the river Styx.

So then . . . BRAIN . . . what’s the deal?

What’s with you?

Why the infinitely repeated dream?

Why the insult and humiliation, night after night . . . the recurring reminders of lack of control? Why, brain, why repeatedly wake me up, panicked, overheated, out of breath?

Don’t you think I know how little control I really have . . . ??!!!

I get it!

I know. I want too much control—every note in perfect alignment, in perfect pitch, flawless melodies and harmonies, all in perfect Bachese / Mozartese / Brahmsese. I totally get the grey-matter metaphor.

I also get that if it quacks like a duck it can in fact be a Lyrebird.

Maybe that’s why our hearts still yearn for 5-Star acoustic concert halls, the world’s best orchestral players—each a worthy soloist, playing only works of genius, conducted by the most perceptive and enlightened musical mind in generations. For half an hour we can suspend the imperfect world we know and surrender to the fantasy of perfection.

You see how it all works? There, underneath all the nice words and phrases of that last paragraph, the same old irony, suspicion, and sarcasm; there’s the Lyrebird delivering his chain-saw (or his cute little duckie) imitation: the real world is kicking right back in, in vengeance; prepping you for yet another repeat of . . . nothing less than . . . your own powerful impotence.

Might I enlighten with a working response to this taunting unconscious?

Time to treat it like a school-yard bully.

You have to, so to speak, as you lay your weary head on your softest form-fitting pillow, and adding in as much withering sarcasm and irony as you can comfortably muster, give sub-mind a piece of top-mind.

Before you go to sleep you tell your brain you will be very disappointed if it chooses to replay the same old hackneyed video again. You don’t want it. You don’t need it. You understand the message.

Speak to it as an equal: You expect the unconscious to be not only more co-operative but much more (infinitely more) adult, (!!!) and creative with its offerings. (!!!)

Astonishingly the sub-mind submits much more willingly than I could have imagined it would.