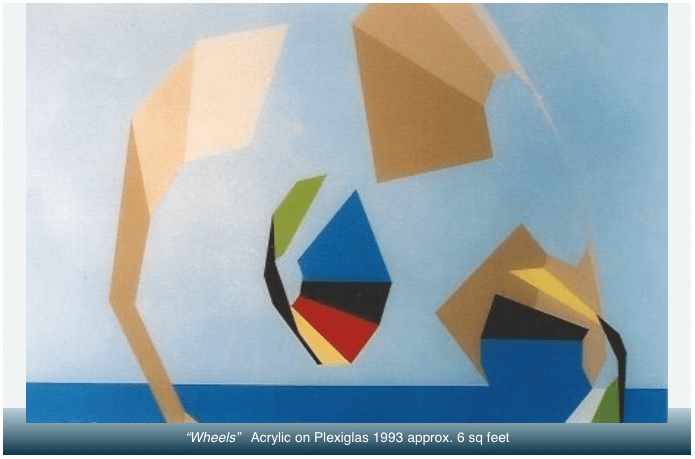

During the weeks I worked on this hard-edged acrylic on plexi in 1993 the Stratford Concert Choir I sang with was very busy practising—for its annual December Concert—an exultant choral piece named “Wheels”.

A local composer, Geoffrey Thompson, had taken text from the prophet Ezekiel and set it to thunderous, rapturous music for organ and choir; very Sci-Fi and dramatic; epic space odyssey music of apocalypse. Ezekiel had apparently witnessed the arrival of spaceships upon his desert landscape, and in a sense, and in his own time frame, had been “blown away” by the noise and spectacle, and the unworldly technological terror that so surpassed his own bronze age.

I couldn’t escape the overt influence of the wheels imagery, but for my purposes, I wanted only an ocean horizon and an infinitely deep sky that would be simultaneously real and abstract. Unlike Ezekiel I was not courting any narrative of imminent danger or terror. I was not intent on predicting apocalypse. I wanted only visual contradictions in which the scale and placement of shapes are unknowable. The beige / tan lenses, or digital camera shutters—just beginning to terminate the use of film—are thus purposefully closer than close and further than far while being at the same time reversible illusions (in the way an etching or drawing by Escher contains stairwells that visually flip inside / outside, upside / downside).

My reward for pursuing my own vision was that immense depth and purity of colour, space, and timeless quietude emerged despite the small physical scale of the painting. In a year or two Mr. Thompson had died and my painting had already gone to sing its French Horn notes from the wall of the friend with whom I sang the First Bass melody lines of Wheels.